David is talking us through creating a coherent curriculum that sticks. It rounds off a day of thinking about improving retention of knowledge and skills. We start by discussing some questions about how we prep students for their exams – do we work harder than them?

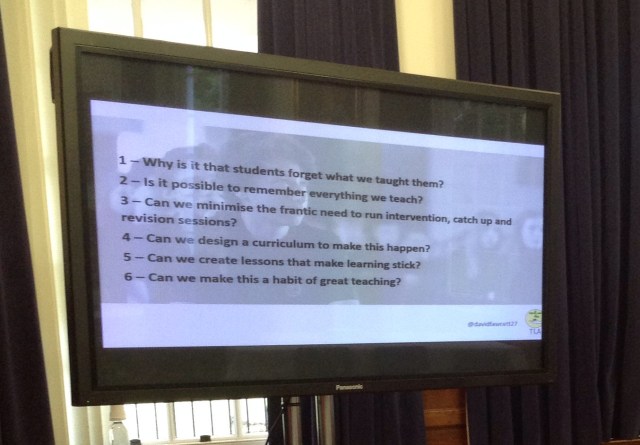

He worked with a colleague to identify the reasons why the results, though good, had plateaued. Was it to do with the structure of the curriculum? They came up with a few more questions to unpick this –

He is quick to stress that their process was about making learning stick better, rather than memorising for exams. This is important, because workload is increasing and the amount of time available for catch up and extra sessions is receding and we’re in danger of becoming a school with a school – one school finishes at 3 and another begins.

We look at schemes of work and learning that we’ve brought with us. Unfortunately I ran out of I time to print anything so have nothing to share. There’s some discussion about hammering threshold concepts in year 7 maths – threshold concepts again!

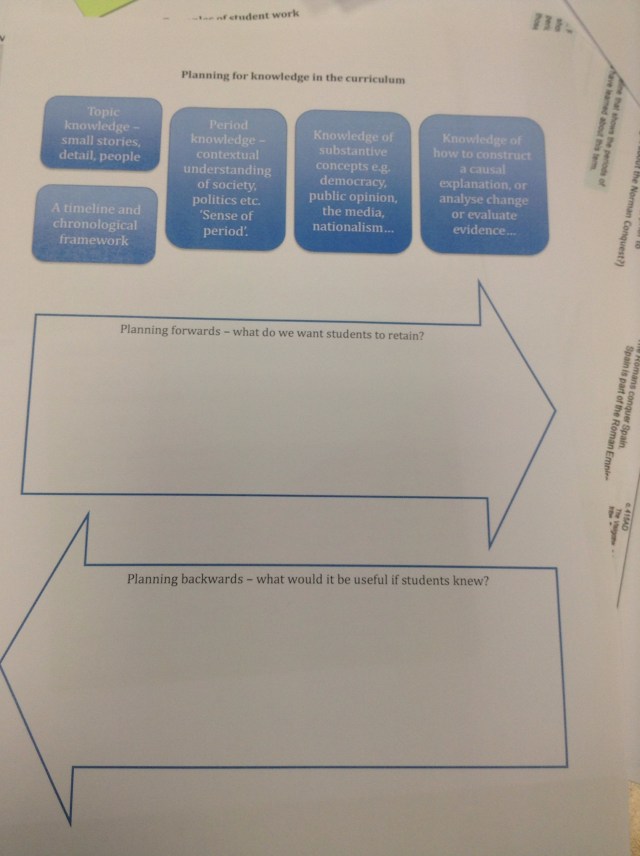

We hear about the work of Robert Bjork on memory – retrieval strength versus storage strength. We should be aiming for high storage, high retrieval in the classroom, but mapping that through our curriculum to ensure it is built in from the very start. David demonstrates this by getting us to demonstrate our schema on Hawaii – things we remember and have picked up about Hawaii.

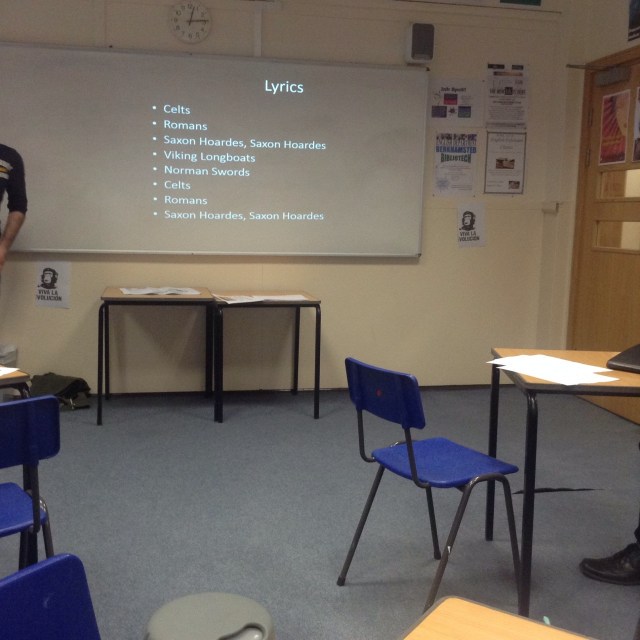

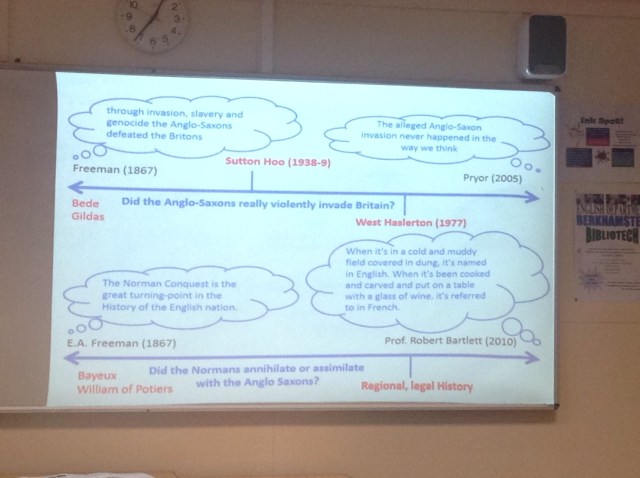

Bjork talks of desirable difficulties which help people to develop these schema. Old knowledge creates foundation for new knowledge, but is that well mapped in our curriculum? We discuss this, with some consideration about whether Gove was right to reorganise the history curriculum chronologically from KS1 (not really – there’s too much in it, imo).

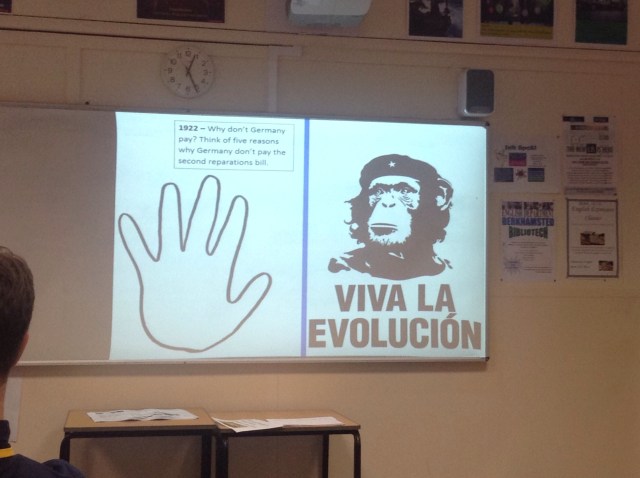

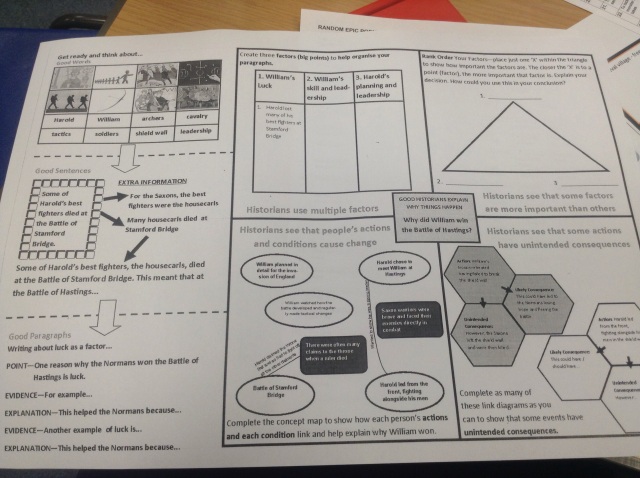

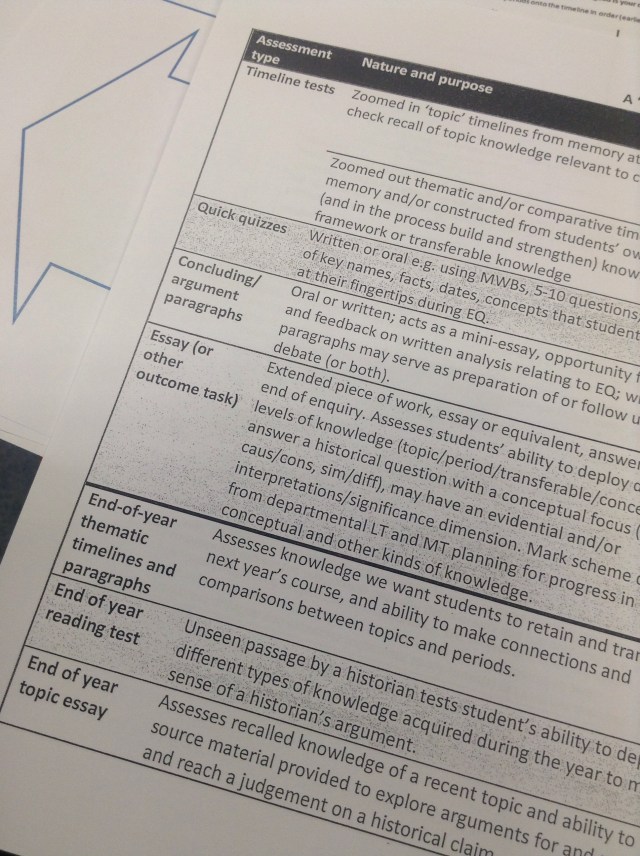

We think about testing knowledge retrieval. The act of testing improves retrieval strength which in turn improves storage strength. 61% remembered after retesting compared to 40% from relearning. Revising should not just be rereading! To ensure there’s not death by testing, questions must fit on one slide with answers on the next slide. Also use multiple choice questions – David’s department pre-test all their students to inform planning and give them a second chance at being successful on the test.

This testing and recapping was built into the curriculum so that students are constantly challenged to remember, which has hugely improved retrieval and retention.

We discuss unit tests vs cumulative tests. Unit tests help to show progress but don’t help them to recap prior learning. There’s a good case to be made here for mixing topics in a test, although this doesn’t really fit with how our GCSE works so will have to think about how it might look in practice.

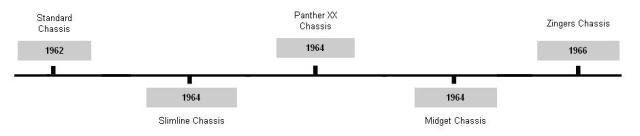

David has added an extra column to the schemes of work to map back to prior learning. I’ve been reworking ours this year and I am really taken with this idea. We share ideas about how we can do these things in our own departments.

David finishes by explaining that instead of reteaching the content, they retest and use a spreadsheet with question level analysis to map where students are succeeding. This is shown by class as well as student, so that seas of best practice are easily visible and can be shared.