I was prompted to return to my neglected blog this term by a couple of things – mainly some work I’ve been doing in school that is an update on work I’ve written about before, but most recently by a post I saw on LinkedIn. I feel as though LinkedIn has become something a little like Twitter was a decade ago. Yesterday, in ye olde Twitter style, I saw a post where someone disparaged their own work from, well, probably decade ago, inviting users to pick out what was wrong with it. It was one of those ‘Compose a tweet’ plenaries but with some cultural references that are now quite dated. Here are some issues I have with this sort of post –

- Pedagogy is still a fairly young science. We still (I don’t think it’s controversial to say this) know more about what doesn’t work than what does work and we’re all still experimenting, as we are likely to be for our entire careers. If you’ve been teaching a while, you’ll know that things are cyclical and that there has to be nuance in the way we interpret our teaching artefacts, so to speak.

- ‘Composing a tweet’ plenaries are not in the same category as thinking hats or learning styles, both of which appeared in the responding comments. Cognitive science research continues to indicate that summarising content, which is the substance of this plenary, is an effective teaching/learning strategy.

- I am very much not a fan of tearing something down to build oneself up (is this what I’m doing here though? How ironic) and this was the problem I very often had with discourse on Twitter. It’s fine to not like something, but too often that manifests as, ‘This is a load of old rubbish’ and the effect of that is to make people feel shamed and a little stupid, and to disengage with the debate entirely. This was evident in the chat people had in Facebook groups when Twitter was all a’twitter – many people saying that they didn’t find it friendly or helpful, and so stopped trying. A better approach: ‘I would probably do it this way instead’ – bring an idea. Create something. Don’t just sneer from the heights. It might get you lots of clicks because we know the algo loves unpleasantness over kindness, but it won’t change many minds.

- I feel like we’re gradually being influenced to weed out the whimsy from teaching and I am staunchly against that. Without whimsy, I would be a lot more bored in my classroom and my personal experience suggests it supports student engagement with my teaching. If you don’t want whimsy in your classroom, that’s fine, but don’t criticise mine. Not that this post did. It was a very benign post tbf. I am just very much not here for the idea that all aspects of teaching need to be uniform.

So onto the original plan for this post, which is a good example of something I created a long time ago that still proves to be good, in some respects, and even better with a couple of changes to reflect more recent research.

I developed a scheme of work called British Diet Through Time back in 2014, at my previous school. It retired at my currently school for a bit but it is now back as we teach the Migrants unit for GCSE, so it provides a ‘migration lite’ unit to year 8 that we can later pin the GCSE content onto. I haven’t taught it for many years, mainly because my timetable, now that I am a full Assistant Head, hasn’t provided me with any Y8 teaching. This year, however, I have two Y8 classes and I have revelled in slipping on this old unit like a favourite hoodie.

I should say that it is urgently in need of some updating, to reflect more recent scholarly terms and now that it serves a slightly different purpose to that it was devised for, but it still just about works. Maybe in my copious free time, I will update it for next year.

When it came to the assessment, three things made it even better this year.

Number 1: the visualiser

The assessment is an annotated timeline. I’m not sure students have got any better at drawing timelines than they used to be, but I have got better at teaching it. To be fair, actually, this isn’t about me but about a tool – the handy and increasingly ubiquitous visualiser. When it was timeline time, I did two things differently –

- I scripted my explanation of how to draw the timeline so that I could ensure I said all the necessary things

- I drew the timeline and displayed the process of me doing this on the board, for students to follow along.

This revealed some interesting things – that students found this much easier to follow than me using a metre stick and doing it on the whiteboard (this probably shouldn’t be a surprise to me); that students don’t all understand how to use a ruler – one or two persisted in trying to use the straight edge of their planner until I pointed out, on the visualiser, that the ruler provides measurements for you (this reminded me of the previous, ‘How do I draw a 7cm line?’ question that blew my mind back in the day); that provided with this model, every single child in both my classes was able to accurately draw the timeline, to the extent that I might have to take it off the marking sheet in the future, because as assessment criteria, it completely failed to differentiate between different levels of attainment in the task.

Who knew that a digital version of what was the coveted technology in 2002, the overhead projector, would become so powerful? It’s almost as if that extremely helpful tool of a bygone age just needed updating for the classroom technology of the current era. I’m sensing a theme here.

Number 2: student knowledge

For some reason, perhaps because they spent considerably less lesson time wrangling their rulers, students had a bit of time to think beyond my very tightly-bounded assessment task. They started asking me about other things they had studied and wanting to add this to their timelines. This led to some interesting conversations about whether these things were relevant to diet in England/Britain: the Black Death, for example, seems to live rent-free in many of my students’ heads and I chatted to some about how this affected the availability of food.

Now I look back at my previous posts and see my old colleague used to begin each year with a timeline, and now my students have demonstrated that they have an appetite for bringing in their prior knowledge, a la Carr and Counsell, and now that the visualiser has enabled a teaching episode that doesn’t make me want to claw my own eyes out in frustration, this is definitely something for revisiting.

Number 3: peer feedback

I’m undertaking an MSc in Educational Assessment at the moment. Over the summer, for an assignment, I read a lot of recent research about what makes the most effective feedback in the classroom. One of the most interesting articles I read was this one. In the experiment, Patchan et al’s Using peer assessment to improve middle school mathematical communication (2022), students received feedback either from their teacher, or from a small group of peers that had received some training on the rubric and how to give peer feedback. The findings did not show that the effect size for peer feedback was greater, but, fascinatingly, it did not indicate that it was significantly behind, either. Although students made errors in the peer feedback, the researchers suggested that the volume of feedback received, compared to feedback from just one teacher, made up for the errors.

This chimed in with another research study, Effects of the Integrated Error Correction Strategy on Senior High Schools Students’ writing proficiency, by Qu and Rahman (2024), where the experiment trained students on self- and peer-feedback, which was used in conjunction with teacher feedback and seemed to have almost the greatest effect size of all the studies I looked at. This interacted with something else I read, or heard, somewhere, about a teacher who had her students complete an assessment and then work in groups to produce a group ‘best and final’ response, which she would mark. I loved this: it cuts down the marking, highlights common errors, encourages self-reflection and error correction.

My brain has been ticking over about this for some months now and I am feeling a big peer assessment project coming on at school, but for the time being, I implemented it small scale with one of my y8 classes. Once they had finished their annotated timelines, students peer-assessed each other’s in pairs or threes, giving two-stars-and-a-wish feedback. Then I gave them ten minutes to fix things about their own work before they handed me in the final piece.

The impact this had on the work was quite noticeable. One of my groups were not keen to peer assess, voting to spend the time working on their own assessments instead, which meant I had something to compare to. The most notable thing was that students did a fantastic job of correcting each other’s spelling and this saved me a lot of time. In some cases, they had written some quite insightful ‘wishes’ and I was able to just tick and agree, rather than set a separate target. I didn’t yet see much change made to assessments following peer feedback, but I think this would be likely to improve as they got more practice.

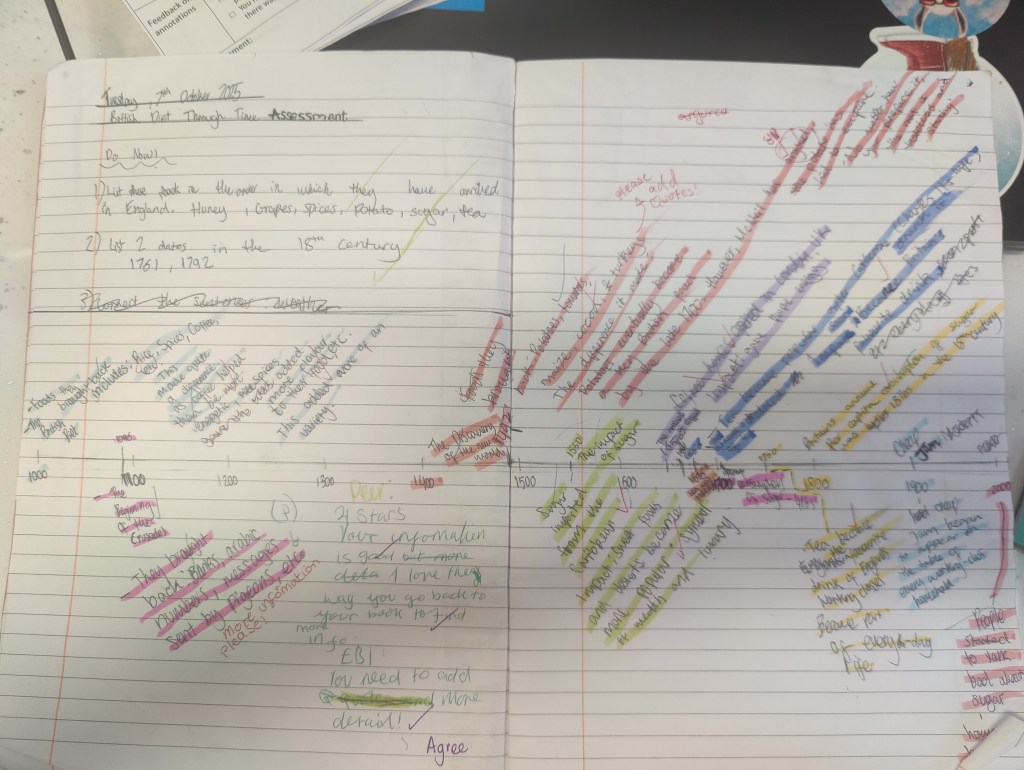

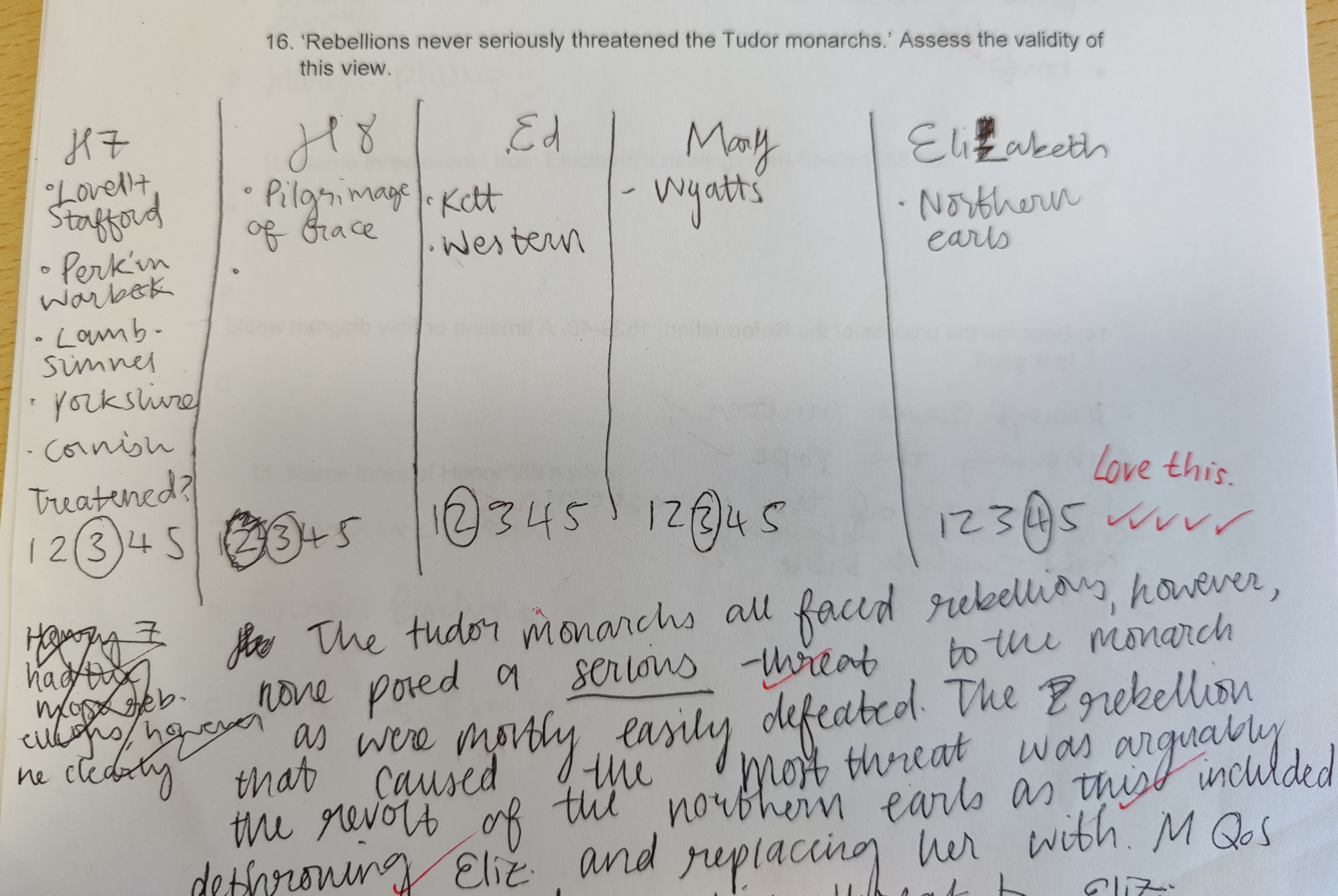

Here’s some peer feedback I loved:

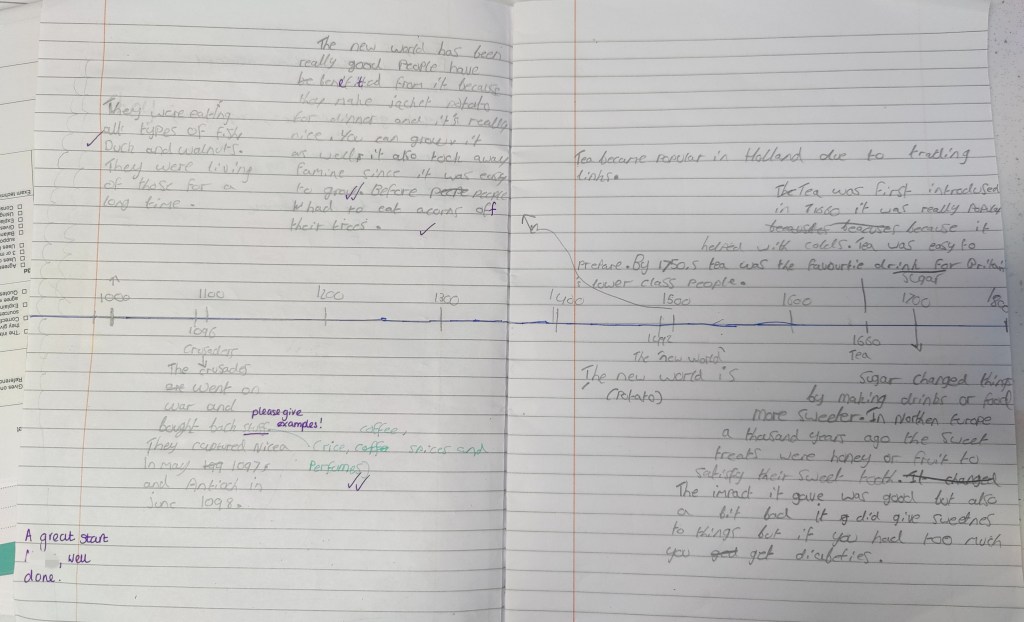

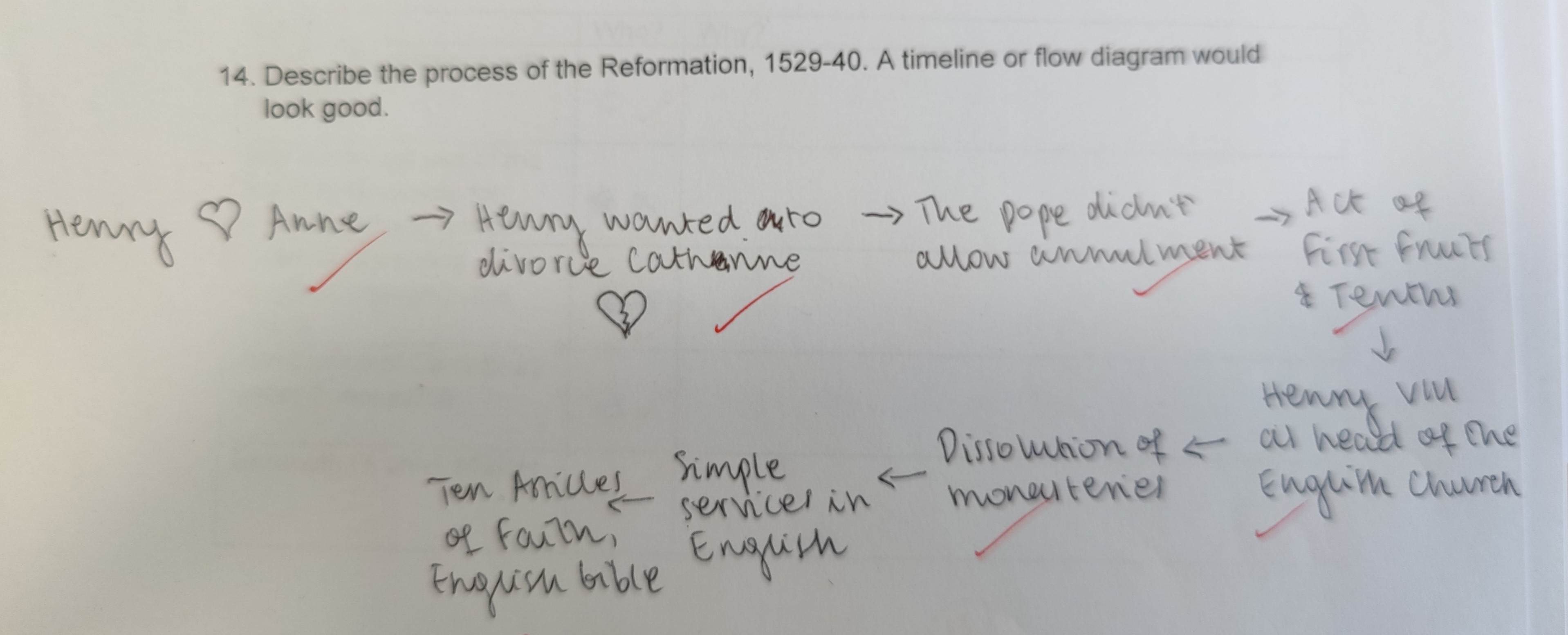

And here are a few timelines I enjoyed – the first received no peer feedback but the second did.

I have to say I love being back in the Y8 groove. It’s the best curriculum year, in my opinion. I’ve just started teaching a Stuarts unit brought in by my newish HoD and I have gone back to my original English Civil War lessons from circa 2004, to see if anything can be salvaged from them. I found that the first lesson contains a ‘Who wants to be a millionaire?’ activity which I had titled, ‘Who wants to be James I?’ At its heart, this is a multiple choice exercise where I spent a long time devising distractors to demonstrate to students the difficulties James I faced succeeding Elizabeth and keeping his subjects happy. I might ditch the game format because that cultural reference is going to be lost on my students now.

But I’m keeping some of the old in. There’s some gold in the old, still.

Another school year is coming to a close. It’s been unique; every year is unique but this one has been significantly different. I’m not reflecting on it much yet because, if I’m honest, I don’t know how helpful it will be to reflect on this unprecedented year because – will it ever happen like this again? I think not. Even if schools close again, we will not be closing for the first time ever. We will be bringing our experiences of the last six months to the table. So, I feel like I need a bit of distance from the events before I can properly reflect on it.

Another school year is coming to a close. It’s been unique; every year is unique but this one has been significantly different. I’m not reflecting on it much yet because, if I’m honest, I don’t know how helpful it will be to reflect on this unprecedented year because – will it ever happen like this again? I think not. Even if schools close again, we will not be closing for the first time ever. We will be bringing our experiences of the last six months to the table. So, I feel like I need a bit of distance from the events before I can properly reflect on it.