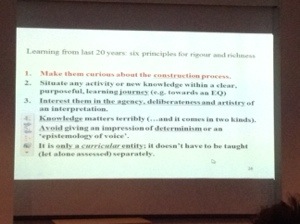

Christine is speaking about knowledge. We don’t spend a lot of time talking about it which gives us bad PR as a profession. We should attend to it much more explicitly and not be frightened of it. The reaction from the middle of last century about the focus on high politics and memorisation, which turned children off and proved inaccessible, is now firmly in the past. SHP was about moving away to a broader range of content and engaging children with the raw materials of history: many good things, although perhaps some babies were thrown away with the bath water.

Therefore, Christine has been thinking about equipping children with enough knowledge to be able to do history really well, and what is enough to go out into the world as an educated historian.

We read an extract from Schama, underlining the words that have a meaning to use due to us having historical knowledge. Recognition and resonance are really bound up with knowledge, and as Hirsch says, a knowledge-rich experience allows for a better understanding of the words. So, when students struggle with a piece of reading, it’s not just a literacy problem – it’s a knowledge problem, too.

We look at some examples of student work and consider why one is better than the other. They are both very good and it is difficult to pin point exactly why one is better than the other. One provides better context, and shows good temporal agility – the ability to whizz around the topic and move back and forth through the timeline. Secure knowledge helps with this and also enables students to step back and be able to look at the whole picture which means they can work with concepts such as (in this case) “the public” and their place in the story. Someone comes up with a good football metaphor, that student A is like a Brazilian footballer in the recent World Cup match who has to concentrate hard on the skill of footballing and showing it off (or the knowledge in the history case) whereas student B is a German footballer who can pass and show their skill without thinking about it and so can instead look forward to where they are going instead of demonstrating the basics. This gets a round of applause….I hope I have characterised it correctly.

Christine makes the point that there is a certain amount of knowledge for each lesson, for the teacher to identify and consider, that cannot be outsourced: things that they need to learn and to know in order to access the rest of the lesson. This is why we need to think of a curriculum design culture, rather than an intervention culture. We need to establish an end point and ongoing content repertoire that helps us to measure what students have learned and ensure they finish key stage three with a clear picture that they can take forward. Patterns of resonance build up: as history teachers, when we see the word Renaissance, it resonates with a thousand stories, and this should be our aim with the students.

Christine talks about fingertip knowledge and residue knowledge. She admits to having a terrible memory for dates (this is comforting because I am also in that boat) and gives us an example of her own: when she taught late 19th century political history, she know all the dates and details of Gladstone and Disraeli, and although she has now forgotten the detail – the fingertip knowledge – but it has left a glorious residue in the sieve of the brain that gives her an enriched understanding of the 19th century and helps her to better understand the 20th century, going forward. What do we need to enable this? Saturation in glorious knowledge. She talks about Ians Dawson and Luff and their role plays and story telling, which give us an enormous amount of knowledge that is necessary in order to make judgements about, for example, Bannockburn’s significance. As teachers, we need to attend to the poverty of students’ brains.

We consider a 17th century enquiry of our choice and identify pieces of knowledge that might be necessary to be successful in studying this topic. Then we consider what knowledge they will need to bring with them: what prior learning will they be pulling on? Then we attempt to classify e types of knowledge: phenomena, people, events…? Categories of our choosing. We struggle with this, having a discussion about knowledge that transcends the time periods, eg treason and conspiracy, and knowledge that needs context, eg the relationship between Catholics and Protestants at the start of the 17th century. Someone else suggests bits and isms.

Christine suggests five:

1. Chronological frameworks

2. Substantive concepts

3. Particular stories

4. Particular personalities

5. Contextual knowledge of the period before

We look at some of Christine’s examples. She said that in her previous department, they decided that they wanted assessment to be driven by what the students needed to know. Thus, a no-revision, no-books timeline as a low-stakes, “fun” test – can you timeline everything we have learned so far this term? Secondly, a timeline done based on revision, with an analytic comment linked into change over time. Finally, a no-notice essay, based on prior learning. These things are also useful things when it comes to checking knowledge. Think about, though, what is useful to you and to them?

A mixed constitution is important for assessment. Timeline tests, and of enquiry substantive outcome activities, mini tasks to show fluency in substantive concepts, routine little checks (I think this would be the scaffolded marking I do in lessons). She reminds us that levels were never intended to be used on individual pieces of work, or even at the end of a year. Using them like this makes it difficult to judge the knowledge in a piece of work, because if you only look at marks you can’t see the knowledge sitting underneath it. For example, when working through piano grades a students might get a pass, a distinction, a merit, another distinction, and then a pass on the the next four grades; so her marks graph will not show progress in terms of marks, but she WILL have a better knowledge of piano playing and have made huge progress in this area. That’s why the levels don’t really work, because it makes it very difficult for us to judge a student’s knowledge.

There is a bit of hope, though, in the form of an end of year exam, which can be quite knowledge focused but can be given a percentage, thus pleasing SLT. We look at some examples from Christine’s pizza assessment group.

Christine finishes with a quote from Daniel Koretz: “Teach to the domain, not the test”. This is a good excuse not to endlessly practice the types of questions on the test: the test just measures the domain, dipping into it, rather than being the point of the learning. Finally, knowledge matters at key stage three because it provides a breadth of understanding that is a vital platform on which to build GCSE knowledge.